ALife: A Particle-Based Artificial Life Simulation

GitHub Repo

Goal

To create a particle simulation that runs on a modified version of physics and chemistry, with some inspiration taken from real life, than can model analogues to real life organic compounds, like phospholipids and amino acids. If analogues can be created and shown to perform similar functions, this would suggest our universes laws of physics and chemistry may not be the only ones that allow life to form.

Requirements

Particles

ALife currently has both neutral and charged particles, both with a position, velocity, and mass.

Future Work

It will also have bonding behavior between various atomic particles, resulting in molecules formed of these atoms. This behavior will be similar to how real life atoms bond, but with much simpler physics to reduce the computational complexity that would result from doing quantum mechanics.

Physics

ALife currently has a physics engine that calculates the forces between charged particles using Coulomb's law and applies those forces over some timestep using the Runge-Kutta method.

Visualization of Coulomb's law between two particlesImage taken from here, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The interaction range between particles is also dynamic; strongly charged particles will apply forces over a larger range until the force is considered small enough to be negligible.

Future Work

The physics engine will need to support the mechanics of molecular bonds, including the forces holding the molecules together and partial charges that form over a molecule.

Optimizations

As with any program run with a large input, we want to improve the performance of the simulation to simulate more particles more efficiently.

Particle Interactions

To find out the strength of two particles interacting, we must first find if the two particles are close enough to interact meaningfully. The naive method for this is for each particle, we check if it's close to every other particle. However, this is a quadratic algorithm and slows down when we want to simulate thousands or tens of thousands of particles.

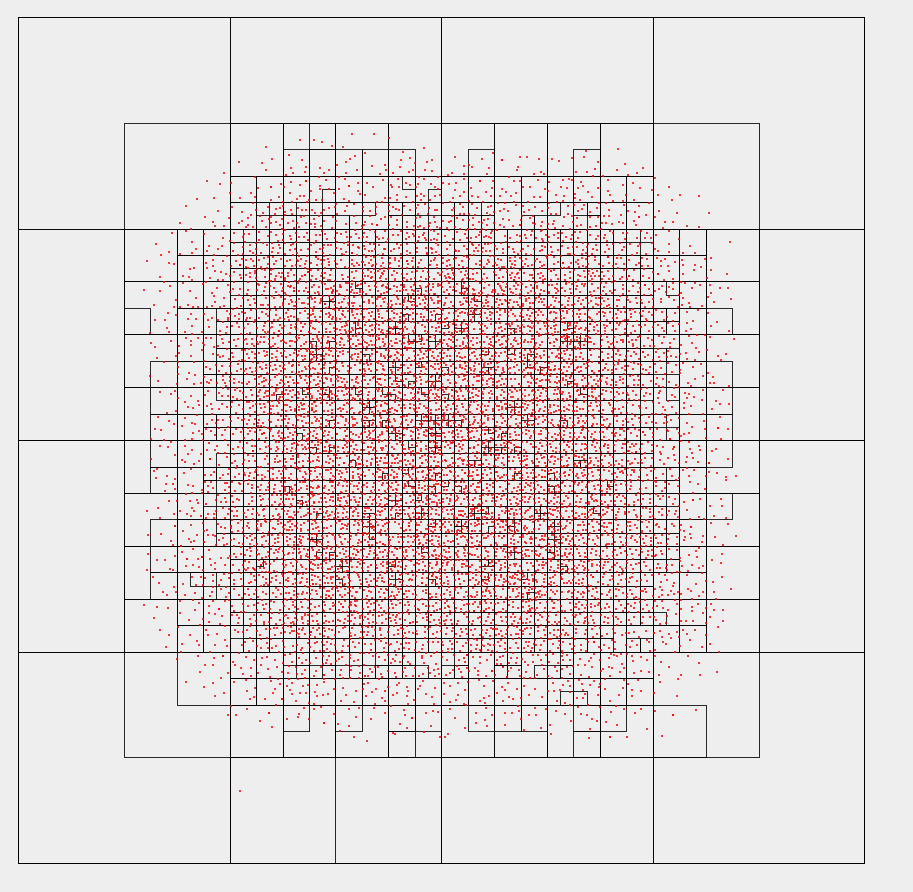

We want to increase the speed of finding neighbors of any particle in a given range, so we can store the particles in a quadtree. This allows us to partition our search area depending on the range. Given some range value, we can find all quadtrees that intersect the bounding box that inscribes our circular range. Then, we only have to search those quadtrees. This also applies to any quadtrees we would search recursively. Instead of searching through a list of all particles, we only search through the particles in nearby quadtrees that are within our bounding box. Then, we can simply check this (usually) much smaller list to see if any particles are within range. I found this algorithm from this StackOverflow post.

On the average case, this is significantly better than the naive approach. Since we can use the partitions of the quadtree to our advantage, we can cut the search area in half (on average) on every step. This gives us the following table:

| Approach | Time complexity (worst case) | Time complexity (average case) |

|---|---|---|

| Naive (checking all pairs) | ||

| Quadtree (bounding box rough search) |

Unfortunately, if the quadtree is poorly built or points are particularly clustered, we will still have to check many point.

Rebuilding Quadtree

When moving particles into and out of a quadtree, some quadtrees can either end up with no particles in them. This adds unnecessary steps when searching through a quadtree, as we have a quadtree whose empty list of particles is never involved in interactions. To fix this, we can rebuild the quadtree. There are two kinds of rebuilding we can do: pruning and merging.

Pruning

If a quadtree has no particles in it and all of its quadtree children are null (do not exist), we can remove that quadtree from the total structure. This can be done by telling its parent to set that child to null. If a quadtree has children that are not null (they exist and have not been removed), we can recursively check their children and see if one of them needs to be pruned. Notably, we recurse first and check after to make sure the tree is pruned bottom-up in a single pass, rather than top-down in multiple passes.

Merging

If a quadtree has some amount of particles in it such that it is not full, we want to move particles from its children into itself to potentially remove children quadtrees. We iterate through its immediate children and try to move one particle at a time from the children until the parent quadtree is full. Notably, we start at the first child (arbitrarily the top-left inner quadtree) and try to move all of its children, only moving on to the next quadtree if that child has no more particles we can move. We then do this recursively on each of the parents children, moving children up the tree bit by bit. We do not need multiple passes as we only stop moving particles if the parent is full.

At the end of every physics tick, we first merge and then prune the root quadtree. This keeps the total number of quadtrees at a minimum, ensuring any searching or iteration through the quadtree is as fast as possible. This merging and pruning takes very little time compared to almost any other operation we perform on quadtrees, like searching or iteration, so the cost of doing it is well worth the reward.

Rendering

To actually see the results of the particle simulation, they must be drawn onto the screen. This is currently done using a JPanel whose paintComponent method is overriden to draw particles and (optionally) a representation of the quadtree. The user can also drag the camera around and zoom in and out.

Snapshot of 10,000 charged particles, with quadtree drawing enabled

Snapshot of 10,000 charged particles, with quadtree drawing enabled

Future Work

The rendering will need to support some kind of UI in the future to

- add, move, and delete particles

- create, save, and load molecules

- show debug profiling information

- show how long the simulation has been running (both in-simulation time and real time)